Self-portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1638-39. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

The 17th century artist Artemisia Gentileschi was a woman who possessed a wealth of strength and intelligence that enabled her to overcome personal adversity and gender-based discrimination to become an acclaimed Italian Baroque painter. The power with which she imbued her female characters led to her rediscovery and a resurgence in her popularity in Western culture during the final decades of the 20th century.

I first discovered Artemisia’s brilliant work during the 1990s on a visit to a local Seattle bookstore. While leafing through the full-page color plates of some of her most arresting paintings, I was captivated by the psychological depth given to the female heroines she often painted as well as her mastery of techniques such as chiaroscuro (the play of light against darkness), adding a dramatic dimension which gives these figures both realism and a larger than life feel.

Early Life

Born in Rome in 1593 to a noted painter, Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia was encouraged from an early age to paint alongside her brothers in her father’s workshop. Orazio recognized early on that his daughter’s artistic talents far exceeded those of any of his sons and groomed her to assist with his most important commissions. At the same time, he recognized her ability to go far beyond mere imitation in her art.

Artemisia’s first life-changing experience was the death of her mother when she was twelve years-old. The loss of the only central female figure in her life at such an impressionable age led Artemisia to use her love of art as a refuge from her loneliness.

Susana and the Elders, 1610, was the first of Artemisia’s well-known paintings. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

Trauma and New Directions

Realizing that nurturing his daughter’s great talent required more than he had to offer, Orazio persuaded his colleague, the painter Agostino Tassi, to tutor Artemisia. Orazio was unaware of the danger in which he had placed his daughter.

At the age of 17 Artemisia experienced her second life-changing experience. Tassi raped her in the Gentileschi house while her father and brothers were away. During the rape, it’s believed that Artemisia cried out for help from the family’s female tenant—named Zumia–who was present in the house at the time but ignored her desperate pleas. Many art historians believe this led Artemisia to have a healthy distrust of women, yet be able to paint them in a way that revealed their complicated nature rather than being portrayed as idealized figures as was the custom at the time.

Accepting the conventions of the time that would label her a sullied woman, Artemisia continued to have relations with Tassi until it became clear that he had no intentions of fulfilling a promise to marry her. As soon as this was disclosed, Orazio was quick to file charges against Tassi in an effort to salvage the reputations of both Artemisia and the family.

During the long trial, Artemisia had to undergo a gynecological exam as well as endure having screws pressed into her thumbs in order to convince the court she was telling the truth. The trial lasted for 7 months and saw Artemisia’s name dragged through the proverbial ‘mud’ among Rome’s elite.

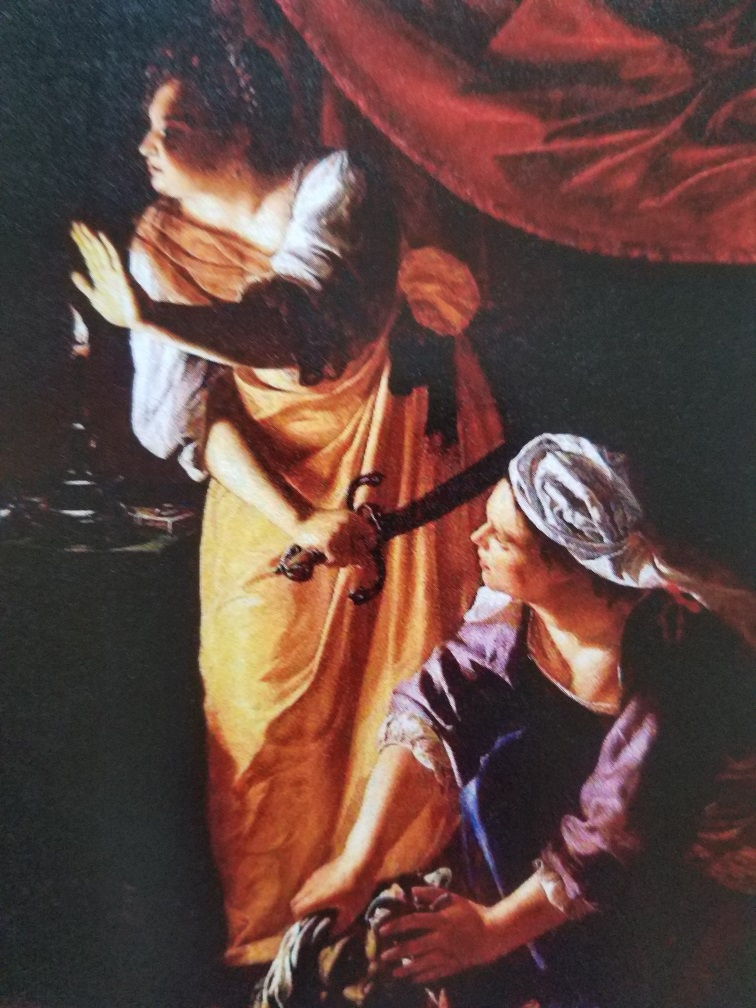

Judith and her Maidservant (detail), 1612. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

Agostino was eventually found guilty of the crime but didn’t end up serving any time in prison, nor was his painting reputation negatively affected by his actions and what should have been a damning verdict. On the other hand, all the burdens of such public pronouncements fell on Artemisia’s shoulders. [This truth is all too familiar in our current world where #MeToo has gained such significance.]

No doubt, Artemisia was devastated by these events and probably felt as if her life was ruined and a career of creating art was forever lost to her. As if to prove her fears real, she soon found that she could no longer get work from her father’s patrons.

In an effort to help his daughter and possibly also to lighten his own personal burdens, Orazio arranged for his daughter to marry a reputedly kind and handsome painter from Florence, lending Artemisia a degree of renewed public respect. At the same time, Orazio hoped that sending her to another city would enable both her personal life and career as a painter to flourish.

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, 1615-17. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

Career as an Artist

Life in Florence suited Artemisia professionally. With the help of her father’s connections, she successfully gained commissions and became highly-regarded in the artistic community. She became a favorite of her patron Cosimo II de’ Medici and often was in the company of the Duke and Duchess of Tuscany. Proof of her high social standing was her acceptance into the Accademia delle arte del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing) as its first female member.

During the ensuing years, and with her husbands full knowledge (if not out-right permission), Artemisia began a romantic relationship with a wealthy Florentine nobleman, Francesco Maria Maringhi. Maringhi became an important source of financial support for Artemisia, her husband and daughter Prudenzia, so named after Artemisia’s mother. However, by 1620 rumors of the affair and financial difficulties caused Artemisia and family to move back to Rome.

Artemisia’s father had just left to work in Genoa and she found life difficult back in Rome. Despite her artistic talents and brave spirit, it was difficult for Artemisia to enjoy the kind of financial and personal success she desired.

Judith and Her Maidservant, 1625. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

In search of larger commissions and to experience the blossoming art scene of Venice, she moved to the city of canals and stately mansions in 1627. Although records from this period of her life are sketchy, it’s accepted that her work in Venice was appreciated for its artistic merits.

In 1630, Artemisia moved to Naples, a flourishing artistic center that had also been the home of many artists such as Carravagio who had surely been a major influence on Artemisia’s painting style, especially his masterful use of chiaroscuro. She was able to secure both private and public commissions during her years in Naples as well as working collaboratively with some of Naples’ most famous artists of the time.

Artemisia traveled to London in 1638 to work with her father who had become a court painter for Charles I of England. Even though her father died in 1639, historical records show that she continued painting at the king’s court for some time before showing up again in 1642 in Naples. One of her most revealing self-portraits, Self-portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1638-39, was included in the king’s private collection.

While the exact date of Artemisia’s death is uncertain, there is evidence that she was still accepting commissions in Naples as late as 1654. Many historians believe she perished along with thousands of her fellow citizens and artist friends when a plague swept Naples in 1656.

Themes and Influence

Its far more than mere coincidence that one of Artemisia’s recurring themes in her work is female strength and the importance of solidarity among women. We can witness the physical and emotional strength her brush strokes bestowed on the two female characters in her multiple renderings over the years of Judith Beheading Holofernes, a favorite subject of her time.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1620-21. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

Just as art historians have celebrated the powerful female ‘heroes’ she painted, they have also noted her work’s absence of conventional femininity. In Susanna and the Elders, painted in 1610, Artemisia makes sure the viewer feels Susanna’s rejection of the pronouncements of the elders. The portrayal of the characters in this popular scene are very different from the compositions painted by Artemisia’s male contemporaries such as Guido Reni’s 1620 rendering of the same scene.

Artemisia’s 1610 version of Susanna and the Elders.

Susanna and the Elders, 1620. Artist: Guido Reni.

Artemisia’s desire was to portray female characters with all the skill and technical acumen employed by male artists of her day, but to ensure that the inner strength she possessed was also reflected in them.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s fortitude and artistic talents helped her confidently navigate the male-dominated 17th century world of Italian art and will ensure that she is remembered as one of the greatest artists of her era or any other.

For better quality reproductions of Artemisia’s most important works, see ‘Selected Works‘.

peace, henry

I also love her work. Excellent post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, what an amazing role model she was for other female artists of her day! Thanks for your comments!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was thrilled to see your post about her. Can’t imagine what she had to do to get recognized or taken seriously in any way in her time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, she was a truly remarkable human being for her time or any other. Thank you for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

Excellent paintings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Dracul!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A story of resilience, an example for us all. Very expressive paintings with Beheading Holofernes striking. Thanks Henry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Marios,

True, Artemisia Gentileschi was definitely the personification of resilience. Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Thanks for introducing me to the work of this female artist: a Master in her own right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Rosaliene,

Happy to share a bit about the life of this amazing woman and her artistic talents. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the follow 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful. Thank you for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Manu,

Thanks so much for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

She’s amazing. I just saw a documentary, Civilization, which told some of her story. What a Dad she had. She was in a difficult position as a woman in a time of inequality and suffered at the hands of a man who didn’t see justice for his actions. However, her father nutured her talent, elevated her, made her career happen, and saw her as a person. Men like this are heros in history!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite an extraordinary family! Thanks for adding your comments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Anna!

LikeLike

Thanks Anna!

LikeLike

very interesting, there were some details I did not know. thank you for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Flavia,

Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

you’re welcome 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on From 1 Blogger 2 Another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Douglas!

LikeLike

Thanks for the reblog!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike